can one tree be more important than a whole museum?

As we are becoming more aware & informed about our role in reshaping our relationship with nature, as architects/planners/landscape designers it’s imperative to deliberate around the planning/designing of built spaces in context of surrounding ecology and to choose a narrative that harmonizes old & new, native & exotic, intrinsic & introduced.

I am sharing excerpts from an article by David Neustein who’s an architecture critic in The Monthly. It’s about Yaluk Langa : a gathering space by a river in Melbourne region. Both:design considerations & the final outcome of this design are equally interesting to read about.

Can a single tree be more important than a whole art museum?

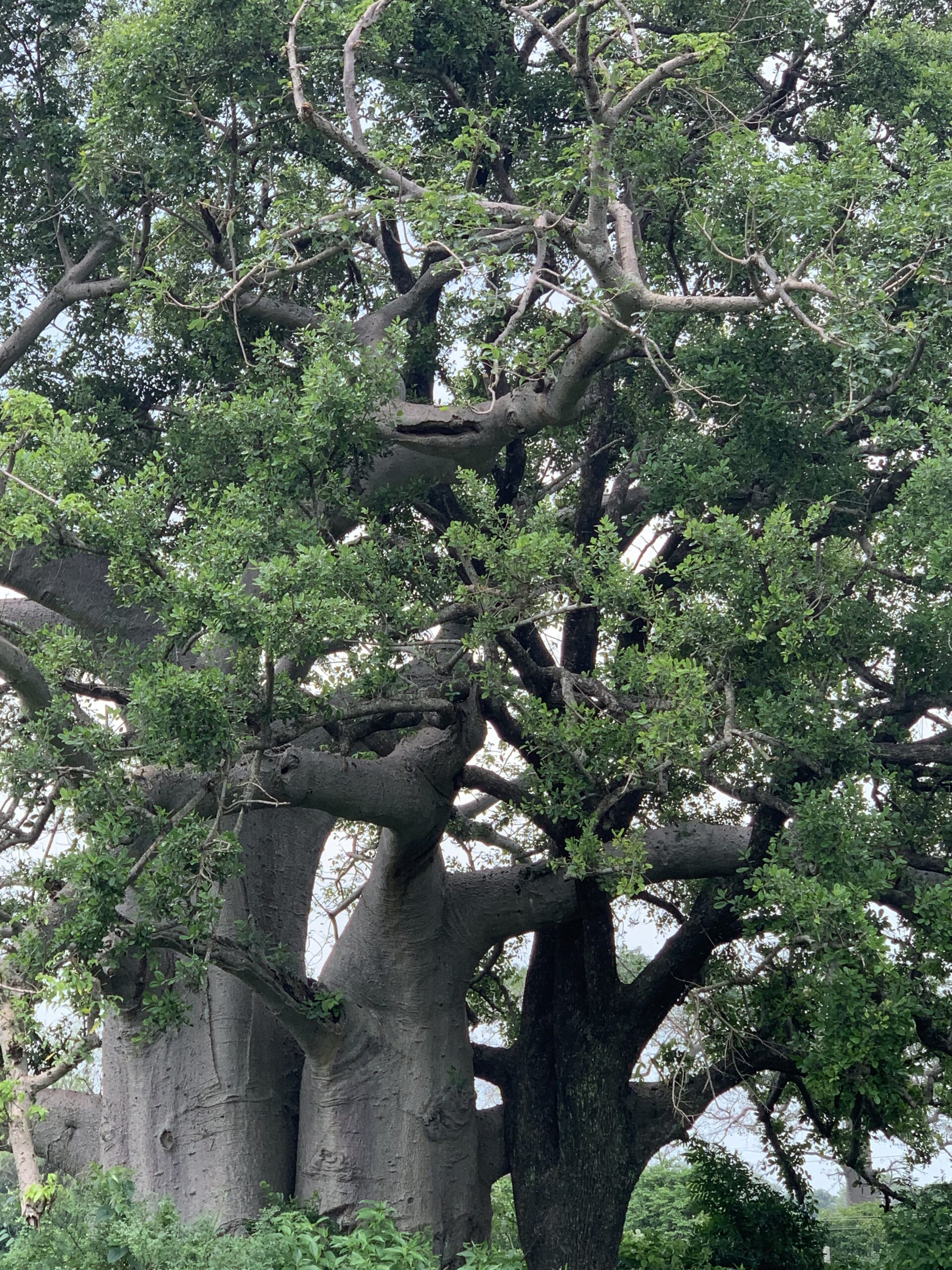

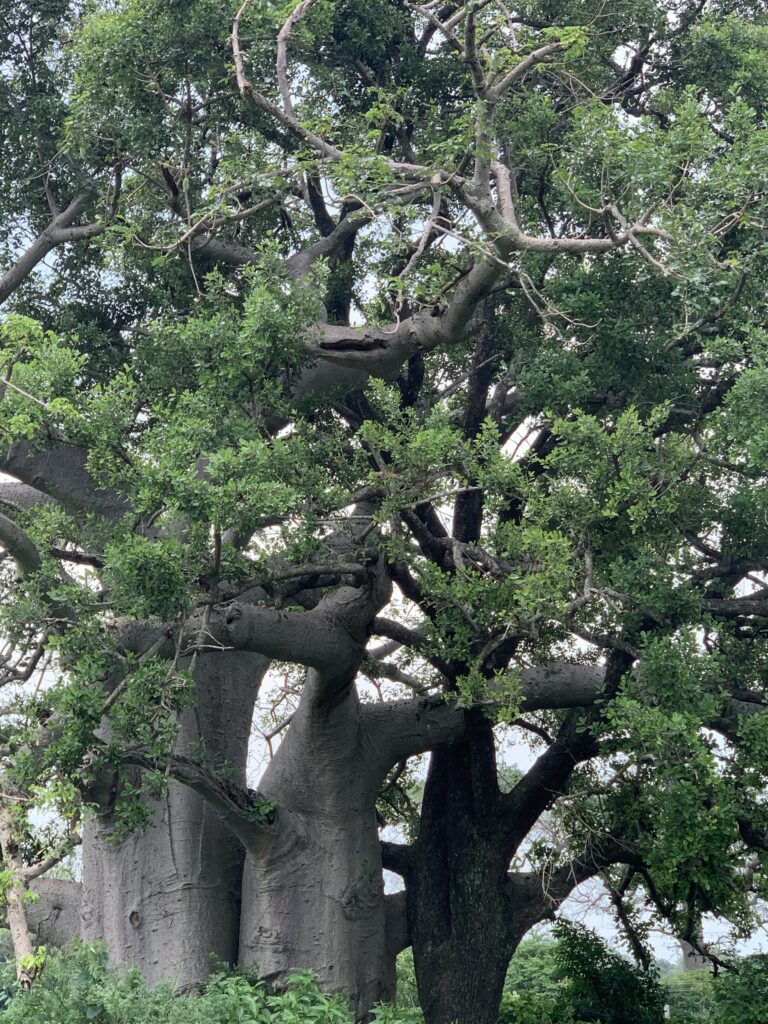

Within the grounds of Heide Museum of Modern Art is a huge gnarled red gum tree named Yingabeal that predates the nearby buildings by 250 years.

Yingabeal, which means “song tree” in the Woi-wurrung language of the Wurundjeri Traditional Owners, is a living monument that marks the place where five ancient indigenous songlines interact. Going by age and spiritual status, it could be considered to be the most significant landmark in all of Naarm/Melbourne.

I must admit that I did not know about Yingabeal’s significance before I began research for this story, nor had I stopped to notice the striking tree on several visits to the museum made over the course of two decades.

A newly created gathering space by the river has brought me to a place of deeper understanding. Called Yaluk Langa, which means “river’s edge” in Woi-wurrung, and which is designed by landscape architects Openwork, this gathering space is the culmination of several years of careful rehabilitation and activation of the museum’s 10,000 square meter river frontage, based on a 2019 framework by Urban Initiatives Landscape Architects in collaboration with Wurundjeri Elders. The location for the gathering space was selected by Elder Uncle Dave Wandin, who identified a clearing in the riverside canopy through which Bunjil, the creator-spirit in eagle form, could surveil proceedings from above.

According to Openwork’s director, Mark Jacques, the brief for Yaluk Langa was to create a space that would draw people to the water and “where stopping and understanding and listening and sensing could happen”. Jacques says that Openwork’s primary contribution was to provide invitation and access to this space, and that its design ethos was to accentuate what was already there and add as little as possible. New elements were derived from just three materials: local mudstone, a sedimentary rock that underlies the riverbed and the gives the Birrarung its distinctive muddy colour; recycled ironbark sleepers; and stabilized gravel of a tone that blends with the surrounding dirt.

While you can’t see the opening to the sky unless you happen to look directly up, sunlight on the ground highlights the gathering space against its shadow-flecked surroundings. Birdsong hangs in the air and wind sends shadows sweeping across the floor. The slope of the bank forms a natural amphitheatre that perfectly frames the tranquil bend of the river. The water is flowing away to the west, carrying your thoughts with it.

Openwork’s gathering space feels occupied even when empty. A semicircular “Pompeiian floor” made from alternating wide narrow mudstone bands inset in the ground forms an auditorium to the water. Other blocks have been arrayed on top of this shape, as if dropped in place during a spontaneous meeting. The curve of the semicircle reciprocates the sweep of the bank and turns the river into a stage. Jacques declares his interest in proxemics, a concept developed by anthropologist Edward T. Hall to define the spatial limits of social interaction. A public space, for example, is limited by the distance that a voice can project, while a teaching space is constrained by how far a calm voice can carry. Yaluk Langa anticipates the way that people come together and has been designed to enable outdoor educational workshops held by and for Wurundjeri.

The layers of timeless and enduring history, colonial occupation and postcolonial inhabitation, made visible in the contrast between exotic & endemic vegetation, make Yuluk Langa more dramatic and episodic than the intact natural landscape. But the way that this new intervention responds to and reciprocates the different features along its path create a coherent and very beautiful spatial story. Described by Jacques as “a very understated henge”, Openwork’s gathering space straddles the line between contemporary and archaic, figurative and naturalistic, foreground and background, heralding new and exciting forms of cultural synthesis.

David Neustein